An article by: Mahbouba Gharbi and Dr. Carola Lilienthal

Introduction

A new trend has been apparent in IT for about fifteen years now: Not only may we learn throughout life, but we can acquire certificates for having expanded our knowledge. Two words in this last sentence should make the interested reader sit up and take notice: “acquire” and “knowledge”.

A certificate must be paid for! Therefore, the first question we want to ask ourselves is whether you can buy a certificate without having substantially increased your knowledge. How are certification procedures organized to prevent such malpractice?

Secondly, we turn to the question of what certificates can or do verify: theoretical knowledge – i.e., everything that can be learned from books, or real practical experience that grows and changes over the years. Should certificates perhaps even have an expiration date? Are there certificates that check whether I maintain or expand my knowledge and experience once certified? Which promises are used to advertise certificates and what can you make of these promises?

Certification procedure

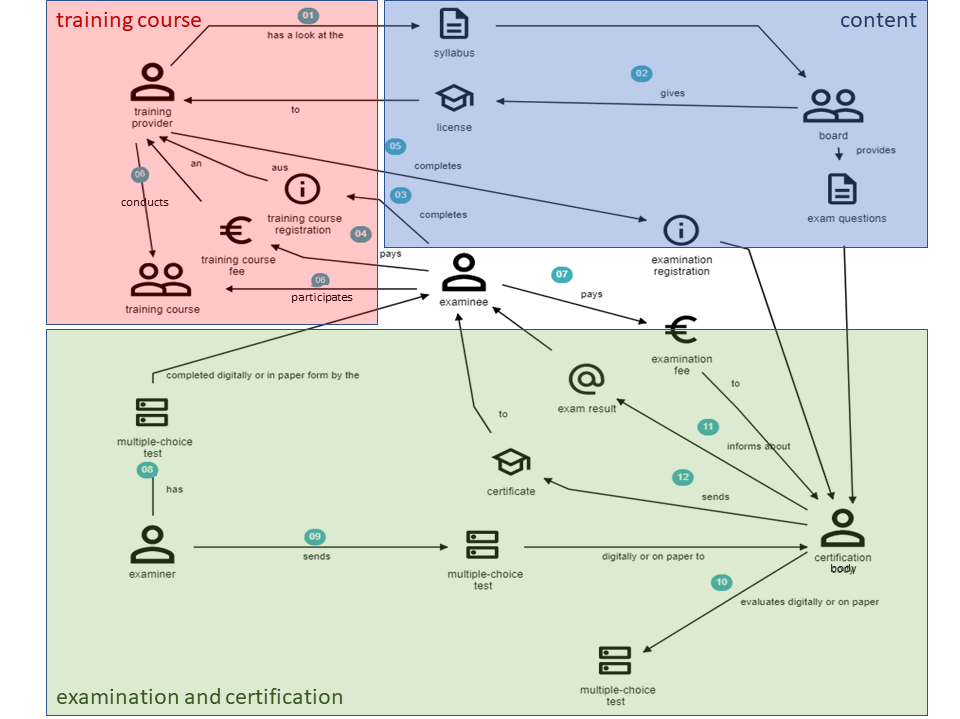

There is a wide range of certificates on offer, yet most certificates and certification procedures are based on a similar process with some comparable variants. Figure 1 shows the basic pattern for certification procedures.

If a training provider wants to offer a training course for a certificate, they first have to consider whether they are able to teach the topics contained in the syllabus (step 1 in figure 1). If this is the case, the training provider must be licensed by the board responsible for this certificate (step 2). With the corresponding license agreement, the board ensures that the training provider implements the board’s syllabus and, if necessary, has the quality of its training materials assured by the board. If you are a prospective examinee looking for a training provider for a certificate, you should always check if the training provider actually holds the required license.

Once the examinee has found a training provider that suits them, they register for the respective training course and pay the training course fee (step 3+4). If the examinee wants to take the exam right after the training course, the training provider registers the examinee for the exam with a certification body shortly before or during the training course (step 5). Certification bodies are authorized for the examination by the board responsible for the certificate. The question pool from which the certification body compiles the examination questionnaires is developed by the same independent board that defined the syllabus for the training course.

Most training courses are organized in such a way that the examination can be taken directly after a training course that lasts several days (step 6). For this purpose, the certification body appoints an independent non-specialist examiner to conduct the exam on site. The exam is administered by a non-specialist examiner in order to prevent them from helping the examinees with the exam in any case.

The certification body receives an examination fee from the examinee for this service (step 7). The examiner has the examinee complete a multiple-choice test (step 9) – either digitally or on paper. They received the tests in paper form from the responsible certification body (step 8). Following the examination, the digital tests are evaluated directly by the certification body (step 11) and the result is announced (step 12). If exam sheets in paper form are used, the examiner sends the completed exam sheets back to the certification body (step 10). There, the answers are evaluated, and the number of correct answers is determined (step 11). The examinee is then informed about their result by email. If the examinee has given enough correct answers, they receive their certificate (step 13).

Figure 1: Certification procedure from the perspective of the examinee [DST]

This process, which at first glance seems relatively complicated for the examinee, was created to counteract the danger presented in the introduction that certificates can simply be bought.

A good certificate is characterized by the fact that the definition of the contents, the training course, and the examination are the responsibility of different institutions that are independent of each other (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Division of tasks [DST]

There are different variants to this comprehensive certification procedure for individual sub-processes:

- Preparation without training course (see figure 3)

- Remote examination (see figure 4)

- Public examination

- Examination at a test center

If an examinee wants to take the exam for a certificate without preparation by a training provider, the examination fee is somewhat higher for most certificates (step 5 in figure 3). Books are offered for most certificates to facilitate self-study (step 6 in figure 3).

Figure 3: Preparation without training course [DST]

For the exam, the examinee has the three alternatives listed above.

Since the coronavirus pandemic, many training courses are offered remotely, and therefore location-independently, so a remote examination is the logical step. For this reason, a remote exam is now offered with many certificates. The exam is taken remotely by the examinee and is monitored by an examiner who connects to the examinee’s computer and watches the examinee with a camera. Thus, the need to travel is eliminated for all parties involved. Procedures that allow for online exams to be taken without supervision, on the other hand, invite malpractice.

Figure 4: Remote examination [DST]

In addition, some certification procedures offer examinees the possibility of attending a public examination or a test center where they take their exam under personal supervision.

So, to summarize the answer to our first question: In procedures that follow the process presented here with a separation of responsibilities and where the exam is taken under supervision, it is ensured that you cannot buy the certificate.

Knowledge or experience?

But what about the second issue? What do certificates verify? Theoretical knowledge or practical experience? Well, this question actually depends on the type of certificate!

Any certificate that only consists of a multiple-choice test merely requests theoretical knowledge. The boards, of course, try to create exam questions that can be answered with practical experience only, but that is very difficult with the multiple-choice pattern.

Certificates that fall into this category usually carry the label “Foundation Level”. The Foundation Level is explicitly advertised by the providers as a basic certificate [FGG10]. The examinee masters a field’s basic concepts afterwards. These basic terms can be learned, their meaning can be explained to the examinee. After the exam or training course, the examinee speaks the language of this domain.

Certificates that build on the “Foundation Level” usually go beyond a pure multiple-choice test. These certificates often carry the addition “Advanced Level”, and sometimes “Professional” or “Master”. For these advanced certificates you have to demonstrate practical experience in some way.

For some certificates you must provide testimonials from your employers for projects that fit the topic of the certificate: e.g., 18 months of testing tasks in projects, or 18 months of project management or subproject management.

Some other advanced certificates include an oral examination in addition to the multiple-choice test. In some cases, there is no training course in the traditional sense, but an attempt is made to simulate a kind of project situation in which the participants work together in the respective field.

Then there are some certificates that come with the unpleasant feature of having to be renewed regularly every three or five years. Either the exam must be taken again, or the examinees have to collect credit points that prove certain activities in the certified domain: Conference attendance, presentations, lectures, article publications. This ensures that the examinees’ experience does not become obsolete.

As far as the question of knowledge and experience is concerned, we note that the basic certificate, the Foundation Level, resembles a theoretical driving test. The theory, i.e., the conceptualization and the rules, are mastered, but there is no practical experience. In this respect, the basic certificates should always be taken for what they are: Theoretical knowledge that must be acquired in order to complete advanced certificates.

Conclusion

If you are looking for further training with a certificate, plan for a basic certificate and corresponding advanced certificates, depending on your current level of knowledge. Only advanced certificates can really testify your practical experience.

Furthermore, you should insist on a proctored examination and only choose certificates with a clear separation of responsibility for content, training course, and examination.

While researching the right training provider, don’t let yourself be fooled by pretty brochures and appearances. Try to get an idea of whether the training managers you are being offered spend most of their time on projects in the field – which means they only earn money with training courses occasionally. If you have found such a training provider, it is much more likely that you will come out of the training course not only with a certificate, but with actual practical advice.

We hope that equipped with this knowledge, you will be able to assess the quality of certificates offered on the market and to identify the most suitable further training for yourself.

[FGG10] Fahl, W.; Ghadir, P.; Gharbi, M.: Vom Sinn und Unsinn einer Zertifizierung für Softwarearchitekten – CPSA‑F: Ein gemeinsamer Nenner für Softwarearchitekten (EN: On the Sense and Nonsense of a Certification for Software Architects – CPSA‑F: Common Ground for Software Architects); Sonderdruck OBJEKTspektrum 11/2010

[DST] The process models are domain stories: www.domainstorytelling.org